Australian and Canadian missed climate targets

- Alastair

- Jan 1, 2019

- 8 min read

We hear a lot about plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, yet comparably little about how we've lived up to past commitments. It's worth taking a look at our past (in)actions and goals as they're important context in which to view current progress.

It's not an optimistic picture. Without a change in direction the Paris target is well on track to joining past failed targets, with voters and politicians again kicking the climate can down the road as a problem for future generations to pay the growing costs of.

The Canadian and Australian governments have made public statements on five greenhouse gas reduction targets (see bottom of the post for details). While most of these targets are the result of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) process and will sound familiar, the Toronto target is rarely mentioned but particularly interesting given current politics. Arguably the first Canadian greenhouse gas emission reduction target, it resulted from the Toronto Conference on the Changing Atmosphere supported by the Progressive Conservative government of Brian Mulroney. It's the only international target adopted unofficially by the Canadian and Australian governments without a signed multilateral agreement.

Greenhouse gas reduction targets consist of four key pieces of information: a baseline year that defines the starting level of greenhouse gas emissions, a target percentage reduction in (or limited increase in) emissions, the year by which a reduction target should be achieved, and --- more on this later, as it's critical to Australia's targets --- a definition of what emissions must be accounted for. Here's the Canadian and Australian emission reduction targets.

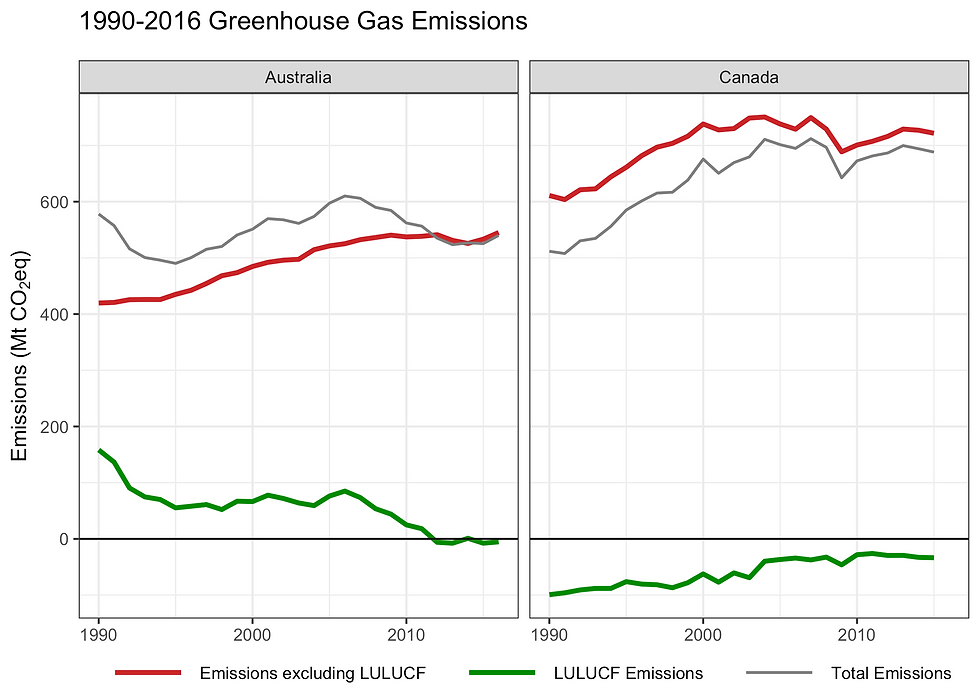

Comparing targets is complicated by the fact that they use different definitions of emissions, especially for land-use, land-use change, and forestry (LULUCF) sources. In addition, countries could sometimes choose whether or not to include LULUCF emissions towards their targets, which further complicates comparisons. Including LULUCF emissions has little impact on Canada’s targets, but a substantial impact on Australia’s.

To simplify the comparison, I’ll start by excluding LULUCF emissions, then discuss how including LULUCF affects Australia. Canada has announced that it intends to account for LULUCF emissions in meeting the Paris Target, but the accounting rules have not yet been decided.

Here’s Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions, reduction targets, and projections of future emissions.

As of 2016, Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions are about 80% from burning fossil fuels, with the other 20% from agriculture, industrial processes, and waste. Emissions rose in the 90’s, and have been pretty flat ever since. I’ve plotted two projections of future emissions from Environment Canada’s Third Biennial Report on Climate Change. The orange “Projected: 2017 Policies” shows expected greenhouse gas emissions with policies that were in place by September 2017, which excludes the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate — PM Justin Trudeau’s signature climate plan. The green “Projected: Planned Policies” includes most of the policies in the Pan-Canadian Framework, showing how the Framework is expected to be an excellent first step towards meeting the Paris target. If the current widespread pressure from conservatives to reduce, or drop entirely, Canada’s climate change efforts do not come to pass, then I’m cautiously optimistic we’ll finally see some real reductions in emissions.

What’s certainly not missing from this picture are laudable climate targets. The grey lines on the figure show a simple reduction path to each target starting from when the targets entered into force (or was announced, in the case of the Toronto target.)

The Paris target clearly comes from a long pedigree of moving climate goal posts, and no substantive reduction in greenhouse gas emissions.

The picture down under

Australia has a broadly similar track record of rising (non-LULUCF) greenhouse gas emissions, repeatedly moving climate target goal posts, and no substantive progress in reducing these emissions. Like Canada, Australia has not come close to meeting any of its targets.

How then, does Australia claim that it has “a proud history of meeting and beating our international commitments on climate change”?

The reason hinges on how greenhouse gas emissions from land-use, land-use change, and forestry (LULUCF) are accounted for. The graph below shows how these can be be a large share of a countries GHG emissions, such as occurred in Australia (primarily due to deforestation) in the 1990’s, or remove emissions from the atmosphere, for example via reforestation, and thus count as negative emissions for the purpose of meeting reduction targets.

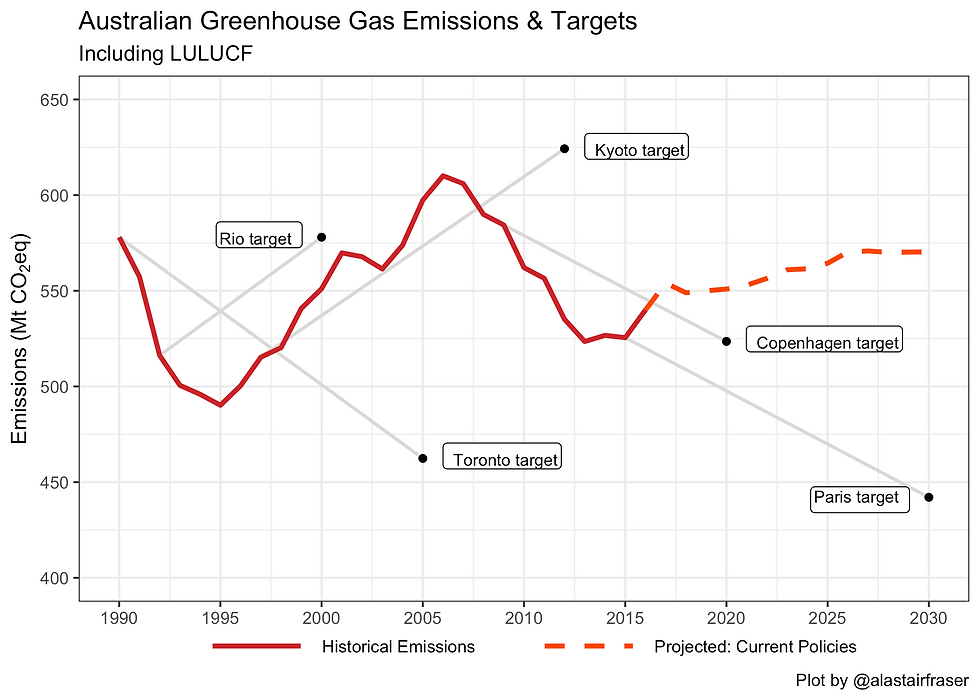

Changes in LULUCF emissions are particularly important to Australia, and especially to the Kyoto protocol target. Australia negotiated one of the weakest Kyoto targets, an 8% increase over 1990 emissions by 2008-2012. Australia also helped negotiate Article 3.7 of the Kyoto Protocol — sometimes called the “Australia clause” — which made their official target easy to achieve. This is covered well here and here. The Australia clause allowed countries with positive emissions from deforestation in 1990, like Australia had, to include some of these emissions in setting their 1990 baseline from which emission reductions are calculated. But by the time the Kyoto Protocol was negotiated in 1997, Australia knew that deforestation emissions had already greatly declined. Australia in effect received credit for having already reduced its substantial deforestation rates, allowing it to further increase emissions from fossil fuels and other sources.

Here’s what the 108% Kyoto target, and other targets, look like when LULUCF emissions are included. By including LULUCF emissions, Australia has achieved it’s Kyoto target.

A caveat is in order here. The Kyoto Protocol used older definitions of emission sources like those from LULUCF, included only some LULUCF sources, had two commitment periods, and defined the target as a 5 year carbon budget rather than a specific goal to be achieved by a single year. As a result, this graph should be seen as broadly representative of the target and reasons it was achieved, rather than an exact match to the target officially declared by Australia. This series of posts by Tim Baxter discusses some of these issues in more detail, and in particular how the Australia clause and credit for LULUCF emissions will transfer over to the Copenhagen and Paris targets.

Regardless of whether LULUCF emissions are included or not, it’s clear that past greenhouse gas reduction targets aren’t a source of optimism for Canada and Australia meeting their Paris commitments.

Data Details

To simplify and keep the comparison of targets consistent, all plotted targets are measured based on the percentage target announced with or without LULUCF emissions as indicated on the plot. I do not use the official targets based on KP or other IPCC accounting rules. In general, using official account rules appears to have little effect on the plotted targets.

Canada

Historical emissions data is from the 2017 National Inventory Report, available through the ECCC Datamart. I use 2017 data to maintain consistency with the projections of future emissions

Projections of future emissions are available from the 3rd Bienniel Report on Climate Change or Auditor General Report Perspectives on Climate Change Action in Canada.

Information on targets comes from a variety of sources.

Toronto target

See “Peter Usher (1989) World Conference on the Changing Atmosphere: Implications for Global Security, Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 31:1, 25-27, DOI: 10.1080/00139157.1989.9929931” pdf here

Reduce CO2 emissions by approximately 20% of 1988 levels by the year 2005 as an initial global goal.

Mentioned in HCSC ENSU report “Kyoto and Beyond: Meeting the Climate Change Challenge”

Target defined in percentage terms only; does not specify LULUCF treatment.

Debatable whether this is a government target; the original statements by Prime Minister Mulroney and his environment minister Thomas McMillan don’t appear to be digitized.

The mycommons ENSU committee report states that the Toronto target was recommended by the committee, but the footnote citation link is broken and I couldn’t track it down. I haven’t bothered to ask the Parliament librarians if they can dig it up, however.

Rio target

Canada signs the UNFCCC at the 1992 Rio Earth Summit. The wording isn’t clear, but does appear to contain a commitment by developed countries to stabilize GHGs at 1990 levels by 2000. See this 1992 GoC Summary

In 1990 Brian Mulroney released the Green Plan which, the internet widely reports, contained a target of “Stabilization of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions at 1990 levels by the year 2000.”

Text from Rio (see 2.c of the agreement) of the UNFCCC appears to allow for LULUCF in defining stabilization goal.

Kyoto target

The A Climate Change Plan for the Purposes of the Kyoto Protocol Implementation Act – 2007 includes LULUCF, and defines 1990 emissions (including LULUCF) as 599 MtCO2eq.

Copenhagen target

Environment Canada states it as 17% reduction from 2005 levels by 2020.

Environment Canada’s Emission Trends 2014 defines the specific levels as Under the Copenhagen Accord, Canada committed to reducing its emissions by 17% from 2005 levels by 2020 with Footnote 1 As economy-wide emissions in 2005 were 736 Mt, Canada’s implied Copenhagen target is 611 Mt in 2020.

Paris target: 30% below 2005 levels by 2030.

Canada’s NC7 (3rd bienniel report) currently specifies 517 as the target discussed and notes that work continues on how to include LULUCF sources and sinks in the target and future emission projections.

Australia

Australia provides only a patchwork of GHG data, summarized on the Department of Environment and Energy page. * This links to the a variety of datasets, including the National Inventory, Quarterly Updates, State, and Sector data. * None of these has a full dataset on AU emissions from 1990 to present. Individual years or state data can be accessed via AGEIS, but not a table of all data. * Using AGEIS link here, CIF/IPCC Sector categories can be downloaded. * Data must be saved by individual year. Sector categories are not unique; for example, there are multiple “other” categories.

Emission projections are available through environment.gov.au here and here

These include an excel file with 1990-2030 emissions and projections, with projections presumably starting in 2017 though the start date isn’t clear.

Australia Targets

See this helpful Australian timeline of emissions targets

Toronto target

20% below 1988 by 2005.

Mentioned in the timeline of emissions above:

Does not specify LULUCF or accounting rules

Rio target

Reduce to 1990 levels by 2000

See UNFCCC Rio document which refers to returning to 1990 levels “by the end of the present decade”

Mentioned in AU emissions timeline, The initial agreed target was a stabilisation of greenhouse gas emissions at 1990 levels by 2000.

Kyoto Target

Two commitment periods

CP1: 108% of 1990 emissions by 2008-2012 period, as described by the Parliament of Australia.

CP2: Not considered here.

For the Kyoto target I use the endpoint of the CP1, 2012.

Uses Kyoto Protocol Accounting Framework

The Australian Government’s Initial Report under the Kyoto Protocol lists the 1990 assigned amount as 554, and the 108% target as 598.

This is close to the Climate Action Tracker target of 592

The revised initial report lists the base year 1990 as 547.7, and 108% target as 591.5, for a 5 year budget of 2957.5

This is consistent with the Climate Action Tracker, but inconsistent with AGEIS data.

Revised Kyoto report: ex LULUCF is 416.155, which is close to the UNFCCC categories (not Kyoto) exLULUCF of 420 and NIR2012 of 415

Partial inclusion of deforestation, but not full LULUCF, in setting baseline appears to cause the discrepancy between estimates.

Given Kyoto target, what emissions count towards meeting this baseline?

Final CP1 report for AU reports base year of 547.7. This gives a 108% target of 591.516, which over 5 years is 2957.58 which is the assigned amount.

AU Kyoto final report is 2008-2012 period (5 years) realized emissions as 2711.153, which is average of 542.

This amount matches, exactly, the “Total (without LULUCF)” declared in Table 2 Review of the 2014 Australia Annual Submission, which is Annex A sources excluding LULUCF for 2008-2012, inclusive.

This is close to the energy only emissions for 2008-2012, reported under Kyoto categories of emission projections.

If for some reason you’ve read this far and want more details, feel free to email me.

Kyoto True-up report: http://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/resources/0924fd96-2f59-49b4-88df-fe49210a3920/files/trueup-period-report-aus.pdf

Cites: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/docs/2015/arr/aus.pdf

Copenhagen target

5% below 2000 by 2020 if there is no global agreement

25% if there is a global agreement

The Parliment of Australia article Copenhagen: a stepping stone: 5%-25% below 2000 by 2020. * UNFCCC Copenhagen agreement

Unclear treatment of LULUCF

Paris target

Australia’s Paris target is “26-28% below 2005 levels by 2030”

Comments